US Presidential Election, Manga Style

Eagle: The Making of an Asian-American President, a generation later

In late July the American presidential election turned from a noir drama into a farce. The Republican candidate survived an assassination attempt and then picked a young running mate, who grew up poor and served in the Marines before becoming a Yale postgraduate. The president did not seek reelection and announced it through X instead of television.

That was how it started. It ended with the Republican candidate returning to his bombastic way, the running mate hounded for being mean to childless women, and the vice president developed a funky fandom. The president was still alive but seemed to be out of the picture.

I have never seen The West Wing and while it retains its charm, it’s not a show that wins everyone. Too idealistic, too Clintonian for conservatives, and too neoliberal, too Clintonian for socialists. We are not having The West Wing situation. Those who are skeptical of Kamala Harris call it the grand season of Veep, where the bumbling Veep falls her way up to the top. Those who are excited about her, the same liberal women from the I’m With Her era, believe this is better than anything Hollywood can produce. The brat is taking the job.

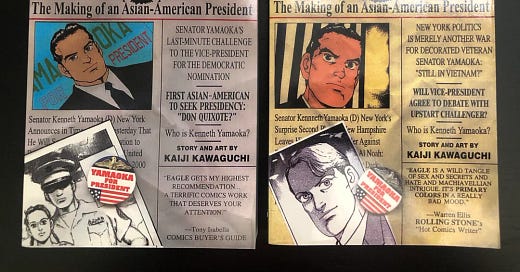

I am here to show you an election fiction you never heard of. A Japanese comic running from 1997 to 2001, titled Eagle. American publisher Viz Media subtitles it The Making of an Asian-American President. It’s idealistic, it’s heroic, it’s great (especially for an Asian), and it’s impossible.

The Eagle is Senator Kenneth Yamaoka (D-NY). Grew up in Seattle, served in Vietnam, and became a lawyer in New York. Married to Patricia Yamaoka (nee Hampton), a New England royalty, and has a hapa son, Alex, and adopted daughter born in Cuba, Rachel. The junior senator enters the 2000 presidential election, being the first Asian American presidential candidate since Hiram Fong in 1964.

Meanwhile, in Okinawa, local reporter Takashi Jo still mourns the mysterious death of his mother Tomiko, when his newspaper, Maicho Shimbun (Mainichi Shimbun) gives him the impossible assignment of following Yamaoka’s campaign trail, at the senator’s demand. Naturally, the Tokyo foreign desk isn’t happy, and the Washington bureau gives him a cold welcome.

Author Kaiji Kawaguchi said he was inspired by the 1993 documentary The War Room on the rise of Bill Clinton and imagined the rise of the Asian (i.e., Japanese) Bill in the up-for-grab 2000 election. Viz Media began publishing the English edition in 2000 in monthly 100-page issues, each cover is a collage of American political photos before a thick five-volume edition (called tankoubon in the manga trade) was issued. The whole saga is over 2000 pages.

The Primaries

Yamaoka is naturally the underdog. His campaign manager is African American Arthur McCoy, and they decided to hire strategist George Tuck (Dick Tuck), who is more of a loner, cynical, and slimmer character than the Nixonian prankster. Yamaoka needs to survive New Hampshire for Super Tuesday, where he must present a challenge to Vice President Al Noah (Mangas are generally not subtle with names). Meanwhile, Jo also serves as a babysitter to the rebellious Alex and the idealist Rachel. They are basically trust fund Bart and Lisa Simpson with ethnicities.

As the plot has it, Yamaoka emerges as Noah’s most serious challenger, and Jo must step up his journalistic stamina and effort, while getting more personally involved with Team Yamaoka. Here Kawaguchi introduces us to American political machinations: Yamaoka must win over the black mayor of New York City, who had a grudge against Yamaoka the civil rights lawyer, and a Texan Democrat. To secure union support, he must choose between two rivals, a jaded Pole (American) and a sneaky Turk (American).

The issue of racism blowback kicks in, but only from white conservatives who hate Yamaoka and McCoy (one can even think that Tuck is Jewish here). The tension of having an Asian American president drives white fathers to boiling points. Just them. Not white mothers, not black or Latino parents, no Korean or Chinese or Arab Americans. One changes his prejudice into support, while another becomes that deranged assassin would-be.

The Convention

Yamaoka goes to the 2000 Democratic National Convention in Denver (the actual convention was in Los Angeles) as a leading contender, leaving “Wooden Al” Noah in a difficult position. President Bill Clayton supports his nomination, but eventually offers First Lady Ellery as a running mate.

Yamaoka secures the cooperation of the mayor of NYC and the Texan Democrats, and even allying with Noah, as Noah agrees to become his running mate, and the convention elected Yamaoka as the Democrat presidential candidate. Ellery slaps Bill backstage.

Jo, meanwhile, investigates Rachel’s biological mother, who accuses Yamaoka of abandoning her (Noah’s rogue strategists crafted the accusation before the convention). And of course, what’s the candidate’s interest in him? The rise of Yamaoka makes Jo realize that no one in America is good, especially as Yamaoka and McCoy admit that they engineer racial tensions to raise sympathy.

The Election

The final part is great on drama but not on politics. The Republican candidate is Richard Grant, a Vietnam ace and an astronaut for Apollo 15, a mixture of John McCain and John Glenn (who was a Democrat). We never heard of the other Republican candidates, and it would have been more interesting had Yamaoka had to face a Yale twerp.

Now distrustful of Yamaoka, Jo gets the whole picture. Eager to follow the footsteps of his dead brother Joseph, Yale graduate Kenneth volunteered in the US Marines, and on his way to Vietnam, met Okinawan woman Tomiko Jo and impregnated her. Kenneth killed a pregnant Vietcong woman attempting to kill him and was seriously wounded before medic McCoy saved him. He continued his life in America with college sweetheart Patricia, being a successful lawyer, and lifted McCoy out of post-war poverty.

Takashi was Yamaoka’s second biological child, and now left with the question of who killed his mother. The executor was Yamaoka’s Canadian spy Robert Duran, who worked not just for the senator but also for his father-in-law.

Eager to push his son-in-law into the presidency, William Hampton decided to remove the Jos, and Kenneth decided to bring Takashi to America following the death of Tomiko. Hence the main tension of the final part is the clash between the Japanese men and the Hamptons. Yamaoka calms a hysterical Patricia, while William poisons Duran before crashing their plane, true to his ideal to clean Yamaoka from all scandals.

The race itself? Grant makes a fatal flaw by saying “Monkeying around” during the televised debate, which Yamaoka pushes as a racist slur. He wins the presidency decisively and we can only hope he could have prevented an ongoing Al-Qaeda plot and a China that is unhappy to see a Japanese man in Washington.

Thoughts

As a manga, it’s epic. No science fiction and fantasy, but there are sex scenes with nudity between Yamaoka and Tomiko and between Jo and Rachel. Kawaguchi writes a plot comparable to American political fiction in the 1990s, mixing a good level of idealism and realism, sans American cynicism.

Nikkei made a comparison graph between Republicans and Democrats, and Kawaguchi subscribed to the same picture 25 years before. Republicans are WASP capitalists, while Democrats are black urbanites. Democrat-controlled American media also made the same generalization in the late 1990s, although at that time affluent white urbanites, including bankers and lawyers, were already Democrat voters.

As Andrew Yang learned, his biggest haters were not white Republicans, but black activists who disliked his policy, white activists who thought he was too centrist, and Asian activists who thought he was a shameful boba, who spoke about math instead of solidarity. In 2000, Yamaoka’s biggest critics would have been black figures who believed that the first African American president must come before the first Asian.

Anti-globalization celebrities and figures would have condemned his military records and WASP in-laws, and despite the depicted strategy to make the suburb question their racism, the suburb could find a solution to remove the elephant altogether. Yamaoka’s difference with Obama was in 2008 Americans were already sick of the Republicans not even McCain could repair it, and the suburban sympathy for a cosmopolitan black lawyer has been built by decades of R&B vinyl, Academy Awards, ESPN, and New York op-eds.

Finally, Kawaguchi had anticipated how online discussion could sway voters, but he was optimistic that anonymous voices would increase the quality of debates instead of…what we’re having today.

Kawaguchi isn’t a worse writer than a typical Hollywood screenwriter (and dare I say, a better artist). A typical Hollywood script will not feature black racism against other races. Kawaguchi sells his product to the Japanese audience, so of course the Japanese American man must win. When American manga readers enjoyed it too as an alternative to their George W. Bush world, it’s just a bonus for Kawaguchi and Viz Media.

Fast forward to a generation later, our current political realities, with all their plot holes and repelling characters, are written by real sickos. It’s not even Veep, just pure nihilism and cynicism.